By Chikondi Manyungwa*

In our recent article titled “WOMEN’S ENGAGEMENT IN AND OUTCOMES FROM SMALL SCALE FISHERIES VALUE CHAINS IN MALAWI: EFFECTS OF SOCIAL RELATIONS” (Manyungwa et al, 2019) we used the social relations framework to analyse women’s participation and the outcomes of participation within small-scale fisheries. In studying Solomon Islands fisheries, Rohe et al (2018) posited that recent development in the gender discourse and feminist intersectional approaches have highlighted that social, economic and cultural characteristics intersect and shape social identities and behaviours. The argument is clear and straight forward that understanding social dimensions in small scale fisheries value chains is important. Thus relevant information on social issues is needed because women’s involvement in the small-scale fisheries sector is influenced by social relations.

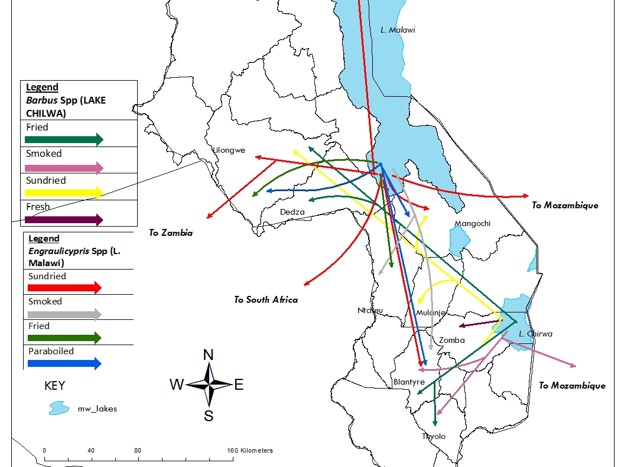

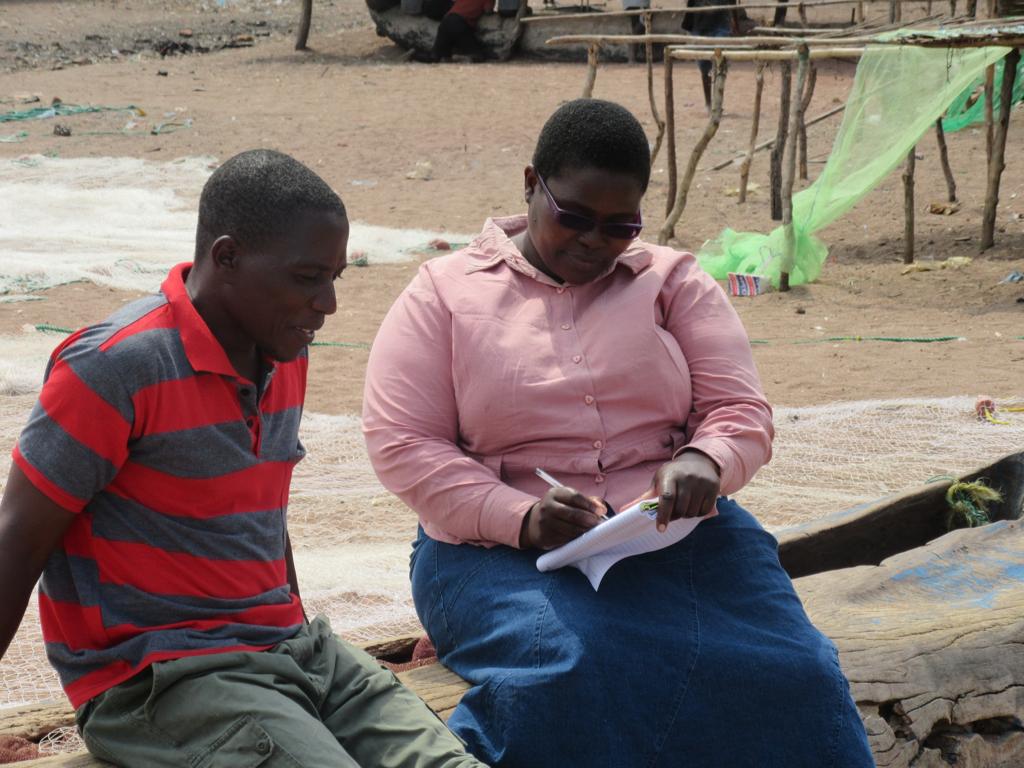

Our Malawi study adopted a case study and qualitative method approach and investigated small-scale fisheries value chains at two sites; Kachulu beach on Lake Chilwa and Msaka beach in Lake Malawi. The research was part of a four-year European Union funded Fish Trade project across sub-Saharan Africa which investigated intraregional fish trade and food security (WorldFish, 2013).

In the analysis we present the understanding of social relations that underpin small-scale fisheries value chains, and we address the question of how social relations affect engagement and outcomes of women who participate in the fish value chains. The social relations approach was useful to the study as it helped in understanding the social relations within the household and between the actors in the fish value chains. The study highlighted self-identified areas of outcomes, going beyond economic outcomes to include empowerment-related outcomes at the individual level, as well as outcomes related to household food security and wellbeing. The study collected information on how households spend the income from value chain activities. Evidence from women’s views show that they spend large fractions of the income acquired from value chin activities to improve household nutrition. For example, at Kachulu female respondents reported ability to buy food and enabling households to become more self-reliant. Women are able to acquire food and are able to feed their children at least twice a day.

In the two fishing sites women play an important role in the small-scale fish value chains and their involvement has differentiated outcomes at individual, household and community levels. In addition, engagement in the fish value chains has brought more positive outcomes for women compared to those who do not participate in the value chain activities. Intra household relations improved as a result of women participating in value chain activities. For instance, it was reported that in households where a woman is engaged in fish value chain activities, women and men engage in joint decision making on the use of the money that accrues from participating in the value chain activities. At Kachulu, female fisher-folk revealed that through engaging in fish value chain activities they were able to become more involved in household finance decision making. At Msaka women said that the joint decision making and planning of the use of the income is a big step forward for the partnership between spouses, the position of women in the family and family life as a whole.

The analysis also presents the challenges that women face as they participate in the fish value chain activities. The study found that women and men face numerous challenges as they participate in small scale fisheries value chain activities. In both case study sites, the key obstacles identified include; gender based discrimination, environmental factors, poor working conditions, care burden, inadequacies in knowledge on trade related policies, social exploitation and socio-cultural factors. For example, with regards to gender based discrimination, the study found that married women are restricted from participating in the role of intermediary actors at Kachulu. While at Msaka it was reported that women are sidelined by the fishers who, when fish catches are low, chose to prioritise selling the fish catch to traders from outside the communities with the view of selling at a higher price. In the context of social exploitation, it can be argued that divorced and single women from outside Kachulu and women who are not spouses of the gear owners and crew members at Msaka are discriminated against based on their social status when it comes to playing the intermediary and fish buying roles.

We found that the level of knowledge on trade related policies among value chain participants especially those involved in fish exports is generally poor.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agrifood Systems (FISH). Funding for this study was provided by European Union funded Fish Trade Progamme implemented through the Lusaka Zambia office. The research was also in part funded by the Gender Equality Studies Training (GEST) programme of the University of Iceland.

*Chikondi Manyungwa is a fisheries professional, employed by the Government of Malawi since 2002. She has made strides in ensuring gender issues are considered in the Malawi fisheries sector. With her skills and knowledge on gender, her significant contributions to the Department of Fisheries include: facilitating the development of a gender HIV and AIDS strategy, contributing to mainstreaming of Gender HIV and AIDS in the Agriculture Sector Wide Approach (ASWAP); and contributing to the mainstreaming of sex disaggregated data in the fisheries data collection tools for the Frame Survey and Catch Assessment Surveys. From 2008-2010, Chikondi was a Fellow under the prestigious African Women in Agricultural Research and Development (AWARD) scheme. In 2013 she obtained a Post Graduate Diploma in Gender Equality (GEST) from the University of Iceland in collaboration with the United Nations University (UNU), where she received the Vigdis Finnbogadottir Award for her outstanding academic achievement in the GEST training. In 2018, she won the inaugural Rosemary Firth award for Best Gender Presentation at the 2018 biennial International conference of the International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade (IIFET).

References

Manyungwa, C.L., Hara, M.M., & Chimatiro, S. K. 2019. Women’s engagement in and outcomes from small-scale fisheries value chains in Malawi: effects of social relations. Maritime Studies,18(3), 275-285.

Rohe J, Schlüter A, Ferse SC. 2018. A gender lens on women’s harvesting activities and interactions with local marine governance in a South Pacific fishing community. Maritime Studies. 17(2):155-62.

Worldfish. 2013. Improving food security and reducing poverty through intra-regional fish trade in sub-Saharan Africa. WorldFish-EU project.

This entry was posted in: Country, Fisheries, Freshwater Fisheries, Malawi, Men, Value Chains, Women